Overview

- Contacts

- Upon Arrival

- Asylum

- Admissibility Interview

- Actions you can take on your asylum case yourself

- Family reunification

- Upon receiving a positive asylum decision

- Leaving Greece

- Women Guide Mainland Greece (booklets)

- Support for survivors of violence and trafficking

- Support for LGBTQIA+

- Forced returns back to Greece

- Germany: return advertisement letters to Greece

- Marriage and Child Custody

- Minor Children

- Health

- Financial Support

- Work

- Reporting a Crime

- Reporting Rights Abuses by the State

- Common misunderstandings and how to prevent them

- Searching for Missing persons

Over the last decade, Greece remains one of the main countries where people enter the European Union and the Schengen Area clandestinely (1) - through the Turkish-Greek borders (Eastern Mediterranean routes from land and sea) and increasingly also over the Central Mediterranean Sea from Northern African countries (mainly landing on Crete and Gavdos Islands). The EU has put a lot of pressure on the Greek government to control these external borders and invested in closing the borders by sending Frontex – border guards of a specialized EU-border agency – and by funding “border security techniques and equipment” such as fences or infrared cameras amongst other things. More than that, it has used Greece to test harmful new migration policies, such as the ‘EU-Turkey Deal’ (2) and the so-called ‘hot spot’ (3) camps at the external borders.

In the last years, many people have been unlawfully returned (“pushed back”) mostly to Turkey, families have been forcibly split over borders and in some tragic incidents people seeking protection even lost their lives.

This European policy focus on migration control and deterrence is also reflected on a national level by the Greek government, which pursues hostile policies against refugees and advocates for the protection of Greece’s borders, detention and deportation. Newly arriving protection seekers sometimes find it hard to access the asylum system. During their initial registration procedures asylum seekers are systematically detained in closed camps without proper access to legal information and lawyers, which can last up to a few months. In general, the only state accommodation available upon completing the registration of the asylum claim is in isolated and controlled camps, far from cities. Asylum laws made over the past years created more barriers to receive protection, such as the admissibility procedure (4). Further dysfunctionalities connected to the states’ mismanagement of funding also severely worsened living conditions, such as the one -year -delay to pay social allowances to asylum seekers throughout 2024/2025, the many months of halt of interpretation- and bus services in camps and the asylum services throughout the country, interruptions in health care services etc. Even for those who receive protection, integration into Greek society is a major obstacle because of the overall situation of the national economy, very limited support available and the lack of a general integration system.

Greece today is harder to reach and harder to live in, yet people find their ways to arrive, endure and survive until they can move on or - in much less cases - to stay and build their lives. Getting papers may currently be easier than in many northern European countries, however, due to the precarious living conditions, Greece remains a transit country in the majority of cases.

In order to receive papers and gain the right to stay in Greece, the usual legal path is applying for asylum. There are also a few other options to get residence permits, such as for survivors of trafficking or for family reunion. Over the last years Greece also is trying to advocate bilateral work migration deals with countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, Pakistan or Egypt in order to bring seasonal workers to fill employment gaps but those programs still present manifold practical obstacles for applicants and numbers of arrivals have remained low. This requires a visa-procedure from those countries to Greece based on work-contracts. Nevertheless, the lack of effective migration paths continues to force most people reaching Greece undocumented.

IN PRACTICE

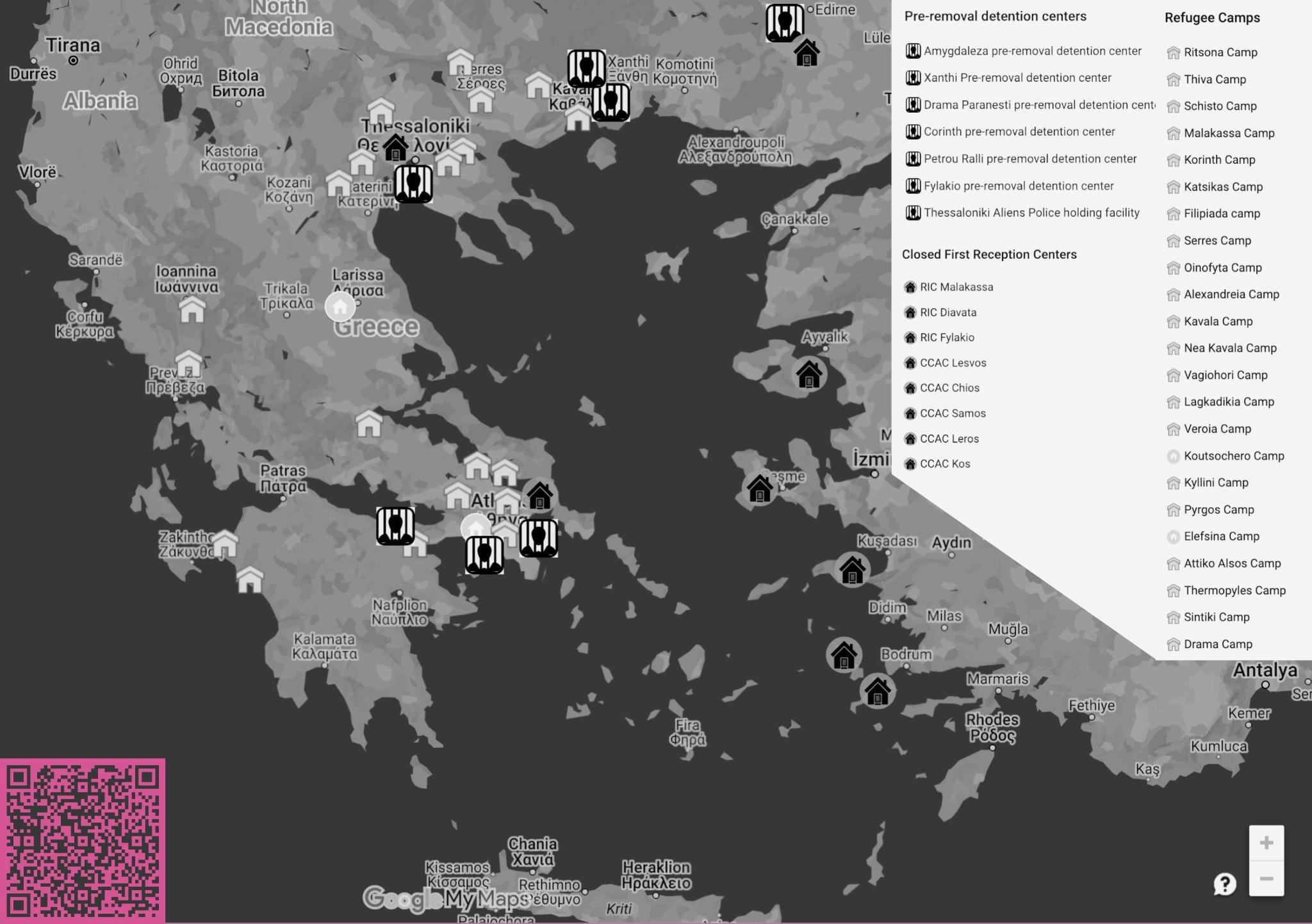

If you reach Greece and want to claim asylum, you register your claim for asylum in a closed centre run by the Greek authorities (on the islands they are called Closed Controlled Access Centres – CCAC, and on the mainland they are called Reception and Identification Centres -RIC). There are CCACs on the five Aegean Island “hotspots” (Lesvos, Samos, Chios, Leros and Kos). There is a RIC at the land border between Greece and Turkey, by the Evros river called Fylakio. If you arrive by land without being arrested, you can only register a claim for asylum in Diavata RIC (for North Greece, including Thessaloniki) or Malakasa RIC (for South Greece, including Athens). People who are detected by Greek authorities on the sea in other areas than those named above (i.e. in Western Greece or on Crete Island) are usually held in a local police station or other closed space for 1-3 nights, registered by the police and then transferred either to RIC Diavata or RIC Malakasa on the mainland. In general, these RICs do not let you inside if you turn up without an appointment. You can book an appointment using this online application ( https://asylum.migration.gov.gr/international-protection-registration/registration_appointment?lang=en ), however sometimes the website does not work, or says that there are “no appointments available”. You should according to law have a right to reception conditions once trying to seek asylum, therefore you can attempt to ask for shelter in one of the open camps and seek their help for the registration of your asylum claim.

Attention! There is no official procedure to accept persons prior to the official asylum application in these (open) camps. You can only ask for their help and tell them that you are homeless and want to ask for asylum and explain your situation.

Attention! In some areas in Greece more near to the Turkish border, people have been reportedly arrested and unlawfully send back to Turkey, which is why most newcomers try to reach camps further away in West-, Central- or Southern Greece.

The registration of your asylum claim within a closed first camp can last up to 25 days according to law, but many times practically exceeds these for some days or weeks. In this time it is very likely that you are not allowed to exit the camp but you can move freely within the camp and use your mobile phone accordingly. During registration you will be photographed and your fingerprints will be taken. You will be asked your basic personal information such as name, family name, birthdate, nationality, mother’s and father’s name, years you attended school, family status, religion and you will be asked to answer very briefly why you left your country of origin and maybe also why you didn’t stay in Turkey. If you hold identity documents of your country (or photos of these) you may show them for proper writing of your data.

Attention! If you present your national passport it will be taken by the authorities and kept during your whole procedure.

Attention! This is not the asylum interview, but the answers you give will be kept on your file and cannot be deleted. This short registration interview is the foundation of your claim for asylum. It is important when being asked why you left your country to state one sentence for each reason. Do not generalise but be specific about your reasons of persecution. You may name more than one reason why you were not anymore safe in your country.

After the registration of your data you will be briefly examined by a doctor. At this stage it is important to explain any illnesses, medications you need, psychological problems, disabilities, pregnancy and also if you are a victim of any form of violence (such as torture, rape, domestic violence or other). This procedure is meant to identify if you are “vulnerable”. Vulnerable persons according to law should be treated with more attention and hold more guarantees during the asylum procedure. (read more about this in the section )

Attention! Many health problems are not visible as well as special conditions or experiences of violence. You should explain these to the doctor as he or she is responsible to register any special needs or vulnerabilities.

*Attention! If you are a parent and your children are underage you have to speak also on their behalf.

Once the registration procedure is completed, you will be handed an asylum seeker card and an appointment for your asylum interview. Ideally you should also receive a tax number (AFM) printed on a white paper. On your asylum seeker card are registered: your personal asylum file number, your asylum case number, your asylum card number and your social insurance number (PAAYPA). With the PAAYPA number you will have access to the Greek public health system – meaning you can book appointments and visit doctors and make examinations in the public hospitals. In the bottom of the card it is noted when you have to renew your card and until when it is valid.

Attention! Never miss the period for the renewal as your file might get closed.

Attention! Your asylum seeker card may show it is still valid but if your asylum procedure is ended negatively, the system still registers the end of validity of your asylum seeker card and you are not protected from arrest and detention with the danger of deportation.

Remember! If you have close family members in another European country, you may be able to request family reunification when you register your asylum claim in Greece (read more about the asylum procedure here and about family reunification here)

From the beginning of your asylum procedure you have the right to seek state support for housing, which then will be provided in one of the 20 camps in all over Greece – upon choice of the Ministry of Migration and Asylum. If you were already staying in one camp before your asylum registration in a RIC, you may be allowed to return there or get transferred to another camp. If you do not wish to be housed in the camp assigned to you and reject going there, you will most likely not get another choice offered and also lose the right for state housing AND social allowances.

It may be hard to imagine but until 2015 there were almost no camps to house asylum seekers and refugees in Greece with very few exceptions (for approx. 2.000 persons only - most of which were lone minors) which resulted in most people being either homeless or forced to rent a spot to sleep in informal hotels around the cities. Following a sudden increase in arrivals of refugees in 2015 when many people found their way from Greece through the Balkans to Northern Europe and with the later closure of these migratory paths in 2016 the Greek government confronted with thousands of refugees whom they suddenly trapped within their borders.

As a response, the state set up an emergency infrastructure with dozens of provisory tent camps all over the country and in a second step also flats offered to around 20.000 of the most vulnerable among people (the so-called: ESTIA accommodation program). Unable to promptly provide adequate reception conditions and services Greece accepted the help of international organisations and NGOs as well as smaller initiatives and individuals from inside and outside Greece. However, gradually the temporary emergency camps were transformed into long-term containerised camps, most non-state actors (civil society) were pushed out, transparency decreased, fences and walls were built around the camps and security gates set up. In 2020, the government closed the ESTIA accommodation program in flats and limited the housing of asylum seekers completely to camps.

Today, the Greek government is in control of all official services for refugees inside the camps. This has generally meant a reduction in quality of reception conditions and decrease in quantity and quality of support services. Employees working in the camps in most of the cases are state employees. At the same time most camp services are understaffed and employees underpaid. However, these employees are responsible of the residents’ support and the first and nearest professionals to address and seek help. Despite increasing funding cuts, NGOs and associations continue to provide important services for refugees, like free legal, psychological or social support, but they mostly operate in cities. Due to the distance of most camps to the next urban centres but also highly limited access to transportation means it may be hard to reach these services physically, but one can initially contact via phone hotlines in different languages or on the organisations/groups social media accounts. (contacts to NGOs are available here)

Attention! Don’t hesitate to seek help from non-state actors outside the camps! Camp employees are usually happy if you seek additional support from outside and it should not harm your asylum procedure or your relationship with authorities in the camp in any way.

If you do not apply for asylum in Greece you will be in danger of arrest and detention with the aim of your readmission or deportation. The Greek police actively control people who they think could be refugees. They often stop people not looking European and ask for papers. Upon arrest and in detention you can still request to apply for asylum. Upon arrest a deportation and detention decision is issued on your behalf. You can appeal this decision within only 5 days upon issuance (see date of issuance noted on the document). However, many times people are arrested and detained and get this detention and deportation decision only later. After the 5-days-deadline you can still appeal against the detention before a competent court and with the help of a lawyer. Concrete danger of deportation to your home country affects those who do not apply for asylum if they come from countries where deportations can be carried out from Greece such as Turkey, Albania, Pakistan or Bangladesh (amongst others). There is no effective danger of deportation for people coming from Syria. If you are from Syria and arrested / detained with the aim of deportation and do not apply for asylum, you should receive a suspension of deportation decision and be released. For people from Afghanistan where deportations are also not feasible there is also currently no effective danger of deportation but also no clear policy. That means your detention may not be ended automatically until the maximum of permitted 18 months, after the change of law in June 2025 up to 24 months, and you may need the help of a lawyer to fight for a prompt release.

There are other countries such as Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo a.o. where deportations are not possible to be conducted and haven’t been heard of. According to official data, in 2024 a total of 2.550 persons were forcibly deported from Greece to neighbouring countries (i.e. Turkey, Albania) or their home countries of which the vast majority was from Albania, Pakistan, Georgia, Romania as well as Turkey. Other nationalities deported in smaller numbers were people from Iraq, Bangladesh, Egypt and India.

The good news: Asylum recognition rates have increased since the independent Asylum authority was set up in 2013 and over the last decade (specifically in the first instance procedure). In 2024, 4 out of 5 persons received a protection status in first instance and the recognition rates reached 99% for Syrians, Afghans, Palestinians and people from Yemen; 98% for Sudanese; and over 80% for Iraqis and Somalis. Although some other nationalities may have (much) lower recognition rates, compared to the European average, there may still be more chances to get papers in Greece than elsewhere.

Another positive development is that, in general, the asylum procedure in Greece is much faster than in years previously. Still, we receive many requests to help speed up asylum procedures – which is understandable – however, we want to emphasize that less time to prepare your asylum case is often not helpful. If you don’t have enough time to seek legal information about the asylum procedure, to prepare your case, find a lawyer and collect any available evidence for your cases and your vulnerability, you may face negative results - especially if you come from a country of origin that does not have very high recognition rates.

If the “admissibility procedure” applies to you, it may also be helpful if you are in Greece over a year instead of rushing to have your interview about Turkey soon after arrival. That’s because there’s a practice of the Asylum Service to allow your claim for asylum to continue in Greece if you have been in Greece over a year and don’t have strong ties (networks, family, friends) in Turkey.

According to the current law, if you are from Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, Pakistan or Bangladesh you will first undergo an admissibility procedure where you will be interviewed about Turkey and if it’s safe for you to return there. This Greek Law unfoundedly claims that people belonging to those five nationalities are in general safe in Turkey. Readmissions to Turkey are not implemented as Turkey does not cooperate with the Greek government to take people back since 30th March 2020. In March 2025, the highest court in Greece annulled this law that designated Turkey as a “safe third country” for asylum seekers from Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, Pakistan, and Bangladesh following legal challenges that had been brought by two Greek human rights organisations. For about two months all affected asylum procedures were halted. Unfortunately, only three weeks after the court ruling a new version of the law was published. Today, in June 2025, the admissibility procedures is in effect again. That’s if you belong to the named five nationalities you’ll still have to persuade the Greek authorities that in your individual case Turkey is not safe. Only after receiving a positive decision, which accepts the fact that you are not safe in Turkey, you can proceed to your asylum procedure in Greece. As mentioned above, since March 2020 no legal returns (readmissions) to Turkey have been implemented. That means that a rejection would currently not put you in real danger to be returned, but it would lengthen your asylum procedure. In case of a rejection you can appeal.

Attention! Often appeals get rejected, but you can then file a subsequent application and if you have completed a year of stay in Greece and do not have any strong connections/networks like family or friends in Turkey than the Asylum Service will issue you a positive decision.

Once your first asylum interview (about your country of origin) is conducted, a decision will be issued. If a negative decision is received, it is still possible to appeal and take further legal steps to get documents, but it is very hard to win an appeal. It is best to prepare as well as possible for the interview in order to receive a positive decision at first instance and not face the difficult appeal procedure.

Attention! Please understand how important your first asylum interview will be for your future. It is highly recommended to take your time and find good support to prepare for admissibility and the first asylum hearing in the best possible way.

Generally, proper information and advice is best from professional Greek lawyers experienced in refugee law that can support your case. All major NGOs supporting refugees provide specialised lawyers for free. As they may have waiting times, seek from the beginning to find a lawyer from one of them. Contact them all asking specifically for legal representation for your asylum procedure (or family reunification), include the names and birthdates of all your family members to your request, your nationality, which languages you speak and where you are living (which camp/city). You also have the right to get a private lawyer if you prefer, but paying a lawyer does not automatically mean that you will have better and faster support. If you search for a private lawyer make sure to chose one specialised in asylum law. A good lawyer you do not recognize by the fact that he or she promises to speed up your asylum procedure but by the fact that he or she makes sure there is effective translation in place, will spend sufficient time asking you questions and understanding your story, your family and health situation and reading through all your documents from the beginning. He or she will explain to you in detail the asylum procedure, answer all your questions and clearly state a fair price and ways to pay.

Attention! You can be only represented by one lawyer in your asylum procedure. Only if you are represented by a lawyer from an NGO, it is possible that other lawyers (from the same organisation) also support your case. You can change your lawyer at any given time by informing him or her, but if you have made oral or written agreements of payment with a private lawyer you may be obligated to pay the agreed price before any change is possible. To be represented by a lawyer you must sign an authorization letter (power of attorney), which should be legalized once you have papers (i.e. the asylum card) by witnessing your signature before a municipality office (in Greek: KEP), camp employees or the police. The authorization will be sent by your lawyer to the Asylum Service where it will be placed in your file. If you lack valid papers you may either put your mere signature (without legalization/official stamp) or - if needed according to your lawyer - you will have to sign in front of a notary at the given costs (around 50-70 Euros). The power of attorney is a paper that gives the lawyer permission to communicate with the Greek authorities on your behalf and work on your case officially.

Because there is limited support in Greece and you may be accommodated far from a city, you have to get active! Ask for information and contacts and seek proper support from lawyers, social workers, doctors, psychologists, educational staff and any experts for your individual needs – we repeat: also outside the camp! Ask others living longer in the area for contacts and develop a network of supporters for yourself to make use of all your options in the best possible way. Write down the names and contact numbers or emails of the professionals and the organisations that work on supporting you in order to connect them with each other (lawyer, social worker, psychologist, doctor etc.). Try to learn/improve helpful languages (Greek, English) and get to know the area around to be as independent as possible and stand on your feet. Keep all your original documents in one file and let professionals supporting you keep copies (not the originals) when needed. Documents can be important in your case, so collect evidence (originals and/or photos) on any hospital stay, doctor visit, therapy, medicine prescriptions, diagnosis, school admission papers of your children and school grades or diplomas, your monthly allowance, your address, tax documents, work contracts, the asylum service or the police, social reports etc. When visiting first time your lawyer bring all these documents along and make him/her aware of any other documents you may have access to from your home country or transit countries that proof your identity, your reasons persecution and vulnerability, so you can receive proper advice about what is most helpful to submit to the Greek authorities for your asylum procedure.

The internet platform of the Ministry of Migration and Asylum has some options to apply directly (without a lawyer and for free!) and in different languages for appointments, copies of your file, change appointments, fasten up your procedure, declare a change of address, phone or email, submit documents, renew your residence permit etc. (see section “Actions you can take on your asylum case yourself”) Take care to ensure your name, date of birth and father’s and mother’s name is recorded correctly – as it can only be changed with an original identity document, if recorded incorrectly. If language or reading/writing or the use of these forms is difficult for you seek help from a person who you are sure can handle the form AND who can advise you on the steps you plan to make beforehand. Do not use the form with someone you are not sure if he or she knows the consequences of the steps you want to make. Specifically, if you plan to fasten up your asylum procedure and ask for an earlier appointment do not take this step before being well prepared. Do not submit additional documents if you are not sure they are helpful for your case. Always seek proper advice before taking any decision. It is also very important to keep your contact information up to date, so that the authorities can reach you. In particular, any email address you give the Greek Asylum Service, the inbox and spam folders should be monitored – important things, even asylum decisions may be sent by email to you. The same goes for your address in case you do not live in a camp.

Despite the infamous difficult conditions in Greece, people who have continued their journey from Greece to another EU country can face return back to Greece. This is a risk for people who have been fingerprinted in Greece or claimed asylum there, as well as people who got positive decisions in Greece and were given a protection status and residence permits. The risk of return depends on the person (your particular characteristics including gender, family situation, age and vulnerabilities) and the country you move on to (different countries have different policies about returning people to Greece, and this is something that is always changing). It also depends on the willingness of Greece to accept you back.

Attention! If you plan to leave Greece after being documented there in any way, before your departure it is vital to document the problems and difficulties you faced while there, collect evidence (photos, medical certificates, official documents, articles on your case or situation etc) and bring it along.

Since the summer 2024 some European Member states such as Germany have turned more hostile towards refugees reaching through Greece and have announced a tightening of border controls, cuts in social support for those arriving with asylum, increased rejections and returns to Greece. Generally, there are two types of returns: A. Dublin Returns of asylum seekers and other people with fingerprints in Greece and B. Returns of people who already hold asylum status in Greece.

Attention! These are two different groups and different characteristics may apply when it comes to the risk of returns.

Concerning Dublin Returns, numbers have been very low in the last three years, but are recently increasing. When it comes to people holding asylum status from Greece mainly the group of “single healthy young men” is at risk of forced returns when it comes to Germany. Other countries such as Switzerland have already implemented occasional returns of single women and currently plan to consider even returns of some families in the future. Yet, there are other countries that have not restarted returns of beneficiaries of international protection.

Attention! In order to protect yourself best, it is very important upon arrival to take a good lawyer who can give you proper information and advice and will help you explain to the authorities of your new country of residence the general and personal problems/human rights violations you faced while in Greece and the reality you would face if you are returned.

(1) The Schengen Area consists of 26 European countries, of which not all are in the EU. The area had largely abolished passport and any other type of border control at their mutual borders, while sharing a common visa-policy. But as a result of the on-going “migration crisis” and with the excuse of security issues following the terrorist attacks in Paris, a number of countries have temporarily reintroduced controls on some or all of their borders with other Schengen states. As of 22 March 2016, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Norway, and Sweden have imposed controls on some or all of their borders with other Schengen states.

(2) EU-Turkey Deal: The EU-Turkey Deal was agreed upon in 2016 and laid grounds for an additional framework of forced returns to Turkey.

(3) Hot Spots: The „hot spot“ approach was developed in Europe. First hot spot camps were opened in Italy and Greece in 2015 aimed at the containment and management of migration. Protection seekers were to be registered through fast track procedures aimed at quick asylum procedures and mainly quick returns.

(4) Admissibility procedure: When the asylum service examines first whether or not a person could be returned to the „safe third country“ he/she travelled through – in this case Turkey. Only after Turkey is in the individual case considered to be not safe, the asylum procedure in Greece is admitted.